Caring about Clothes

Five years ago, I was the guy that would judge people who cared too much about clothes. My disdain came in two flavours. On the one hand, I saw it as a character flaw, where the misguided pursuit of status or excitement was leading people to spend too much money on things that didn’t really matter or improve their lives. Through this lens, I saw people kind of like gambling addicts, at the mercy of the uncontrolled urge to buy things and waste resources they often didn’t have.

On the other hand, I equated an interest in clothes with a shallow valuing of material things and a surrender to the lowest means of judging others, through obvious status signals. I remember seeing a co-worker bring a Prada bag to work and thinking it was so trashy.

I remember the feeling of these convictions, of knowing that I was right. I grew up in the small town of Saltspring Island on the west coast of British Columbia. I moved to Vancouver for university and it felt, to me, like a massive city. I became aware of so many ways in which life was different. Looking back, I can see how the experience of these differences became a big part of my identity.

On Saltspring, status wasn’t strongly connected to material wealth in general, nor to clothes in particular. My uncle is a well known and and liked member of the community and he walks around town looking like a homeless person. Nobody does a double take. People stop and talk with him. It’s just fine.

I painted houses growing up and would go into town on lunch breaks in paint splattered, ill-fitting shorts and beat up basketball shoes, and feel totally comfortable running into friends or talking to girls.

When I moved to Vancouver, I quickly noticed how different things were. I pictured my uncle standing at the corner of Burrard and Georgia among all the folks going shopping or walking to their offices. I was sure people would judge my kind, fun and unique uncle, and would probably avoid him.

Throughout these years, the appeal of nice things was always under the surface. I could sense the imagined life and identity suggested by things, and the power of wearing something to shift how you feel and are perceived.

I remember a trip to Mexico with my family when I was in elementary school. I spent an inordinate amount of time trying to find the best reproduction Rolex. I wanted it to feel heavy, and to have the right movement and design.

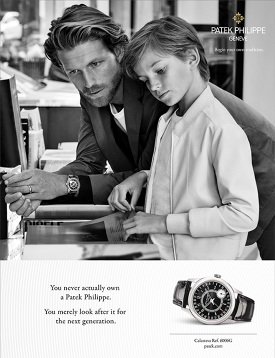

When I got a bit older, I started reading the Economist, and every issue had a Patek Philippe ad on the back. The image was always of a father and son, the father dressed like a businessmen on the weekend, in a nice home or car, with nice things all around. There was a world there, a safe and stable world, where a person could exist in that house, with those clothes and that watch, and have the unfolding of their life be significant.

Patek Philippe

As I became an adult I decided that this was manipulation, and that I knew better.

Two changes opened the door to an interest in clothes. One was learning how to shop online. I never did it before COVID. The whole idea of buying something before trying it on felt absurdly risky and wasteful to me. I didn’t like the idea of shipping things around the world multiple times just to get a slightly better fit or style. Who was I to command such logistical feats for something so frivolous?

I also didn’t know how. I didn’t know that you could measure things and get really specific about fit and style.

But during COVID I wanted a shirt jacket. I spent hours searching and found something in the colour, style and material that I wanted, at a price I could afford. That I could do this from the comfort of my couch was a revelation.

I always hated the experience of shopping. Going into a store was like entering an escape room. The goal is to walk out with something great, that fits, that’s exciting, that’s on sale. You try something on. You wonder, can I wear this? Am I this guy? You buy it because you want to win the game. You try it on at home and immediately regret it. You don’t want to return it because that feels like defeat.

Online, at home, you can think, imagine, consider.

By this time I also, finally, had a bit more money. It started to occur to me that I could get something nice for myself, even if it wasn’t an absolute necessity. Buying something wouldn’t mean being destitute in retirement. There was stability.

Being young felt precarious. It felt like you needed to amass retirement savings to be safe. My judgments about frivolous consumerism were the belief system that supported the saving behaviour that I needed to feel secure.

It felt so liberating and indulgent to buy myself something that I wanted. Buying my first pair of 200 dollar jeans felt like a leap of faith. That sounds a bit ridiculous, but it’s true. It was a faith that I would be ok without that $200 in my bank account.

These early experiences inspired a whole journey of learning how and what to buy. That imagined life and identity can so easily be hijacked and manipulated by brands and media. Buyers remorse and unsatisfying purchases are so common. But you can learn about yourself, what you like to wear, and what you look good in. It’s super satisfying to win the game when you take home something that you actually like, that makes you feel good and that you’ll wear for a long time. It’s fun to try new things. To see how they feel, and how other people react.

I still judge the Prada bag a bit. To me those luxury brands are such obvious status symbols. It’s not subtle and doesn’t seem to offer enough flexibility to play with and make your own. And they’re so ridiculously expensive. But I’m willing to admit my ignorance. I actually don’t know much about it. Who knows what revelations the the next few years will hold.